Intuition of AI

Artificial intelligence is no longer a niche area of research; it is a foundational tool in modern software engineering. For professionals in the technology industry, understanding the mechanics behind these systems—rather than just their APIs—is becoming a requisite skill. This book aims to bridge that gap. You will learn exactly how different classes of AI work conceptually, alongside the basic structures of their implementations. We will trace the evolution of algorithmic intelligence, moving from the explicit logic of Search and Evolutionary Algorithms through the statistical principles of Machine Learning, and finally into the complex architectures of Deep Learning and Generative AI. By understanding these foundational principles, you will be better equipped to reason about, implement, and innovate with the systems that are reshaping the world. You can expect to learn with relatable analogies, practical examples, and hand-drawn illustrations. Let’s crack open the black box.

What is Artificial Intelligence?

Intelligence is a bit of a mystery. Philosophers, psychologists, and engineers all view intelligence differently. Yet, we recognize it everywhere: in the collective work of ants, the flocking of birds, and our own thinking and behavior. Great minds have long debated the nature of intelligence. Salvador Dalí saw it as ambition; Einstein tied it to imagination; Stephen Hawking defined it as the ability to adapt. While there is no single agreed upon definition, we generally use human behavior as the benchmark. At a minimum, intelligence means being autonomous and adaptive. Autonomous entities act without constant instruction, while adaptive ones adjust to changing environments. Whether biological or mechanical, the fuel for intelligence is always data. The sights we see, the sounds we hear, and the measurements of our world are all inputs. We consume, process, and act on this data; therefore, understanding AI begins with understanding the data that powers it.

Defining AI

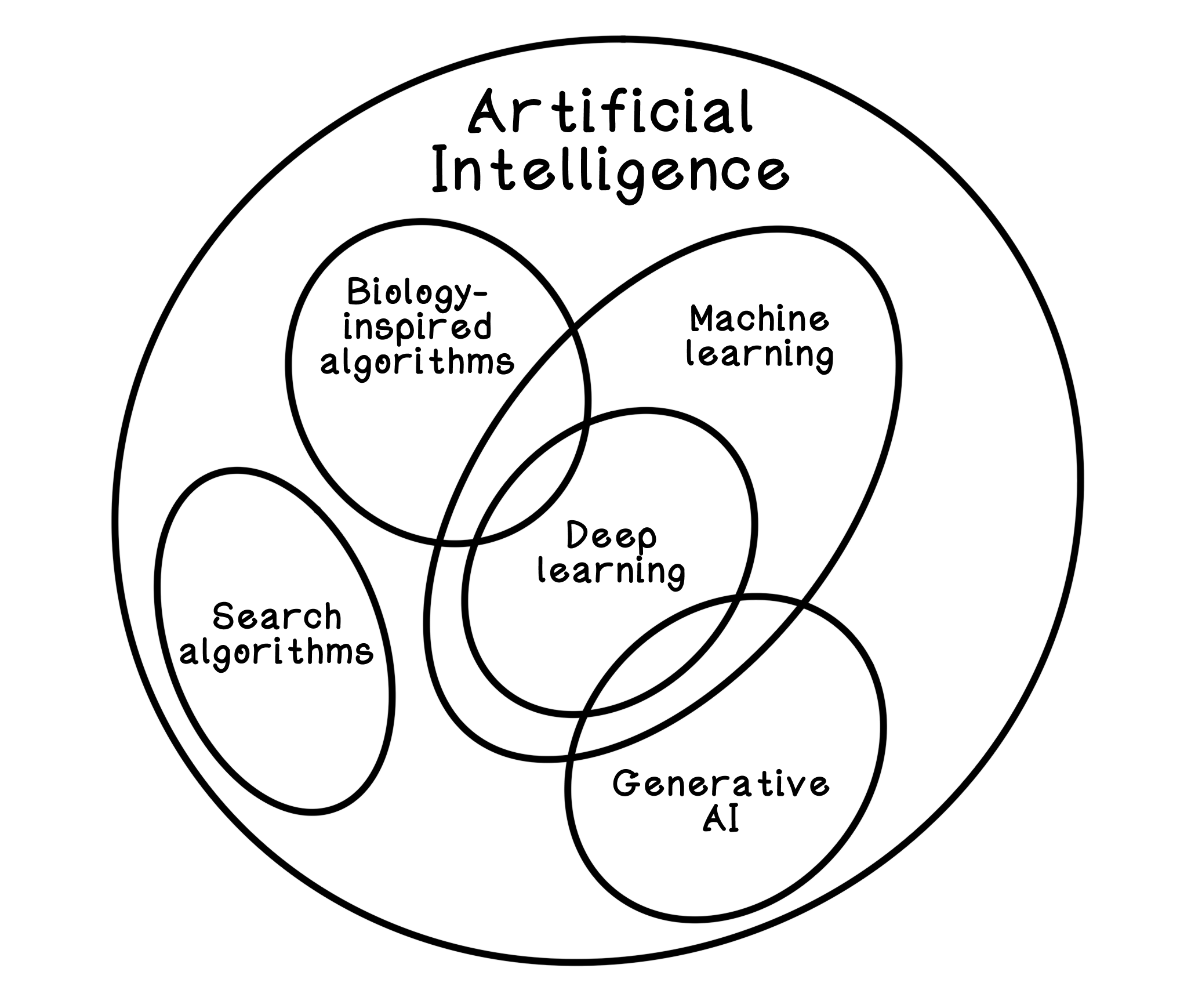

Generative AI, like natural language models and chatbots, has become the “public face” of AI. However, in research and practice, AI is far more diverse. The complex systems we use today are built upon many foundational algorithms geared to solve different problems— ranging from specific tasks, like effectively searching information, to general challenges, like understanding language. Throughout this book, we will be exploring these algorithms, their use cases, and developing the intuition leading to modern machine learning, artificial neural networks, and generative models.

For the sake of sanity, let’s define AI as systems that perform tasks typically requiring human intelligence. This includes simulating senses like vision and hearing, or mastering language to reason about complex problems.

-

Playing and winning complex games

-

Detecting cancer tumors from body image scans

-

Generating artwork based on a natural language prompt

-

Autonomous self-driving car

-

Chatbots encoded with the history of information on the internet

Douglas Hofstadter famously quipped, “AI is whatever hasn’t been done yet”. A calculator was once considered intelligent; now it is taken for granted. Whether an algorithm fits a strict academic definition matters less than its utility. If it solves a complex problem autonomously, it belongs in our toolkit. The algorithms in this book have been classified as AI algorithms in the past or present; whether they fit a specific definition of AI or not doesn’t really matter. What matters is that they are useful and intuition about them forms a robust understanding from foundational to sophisticated applications.

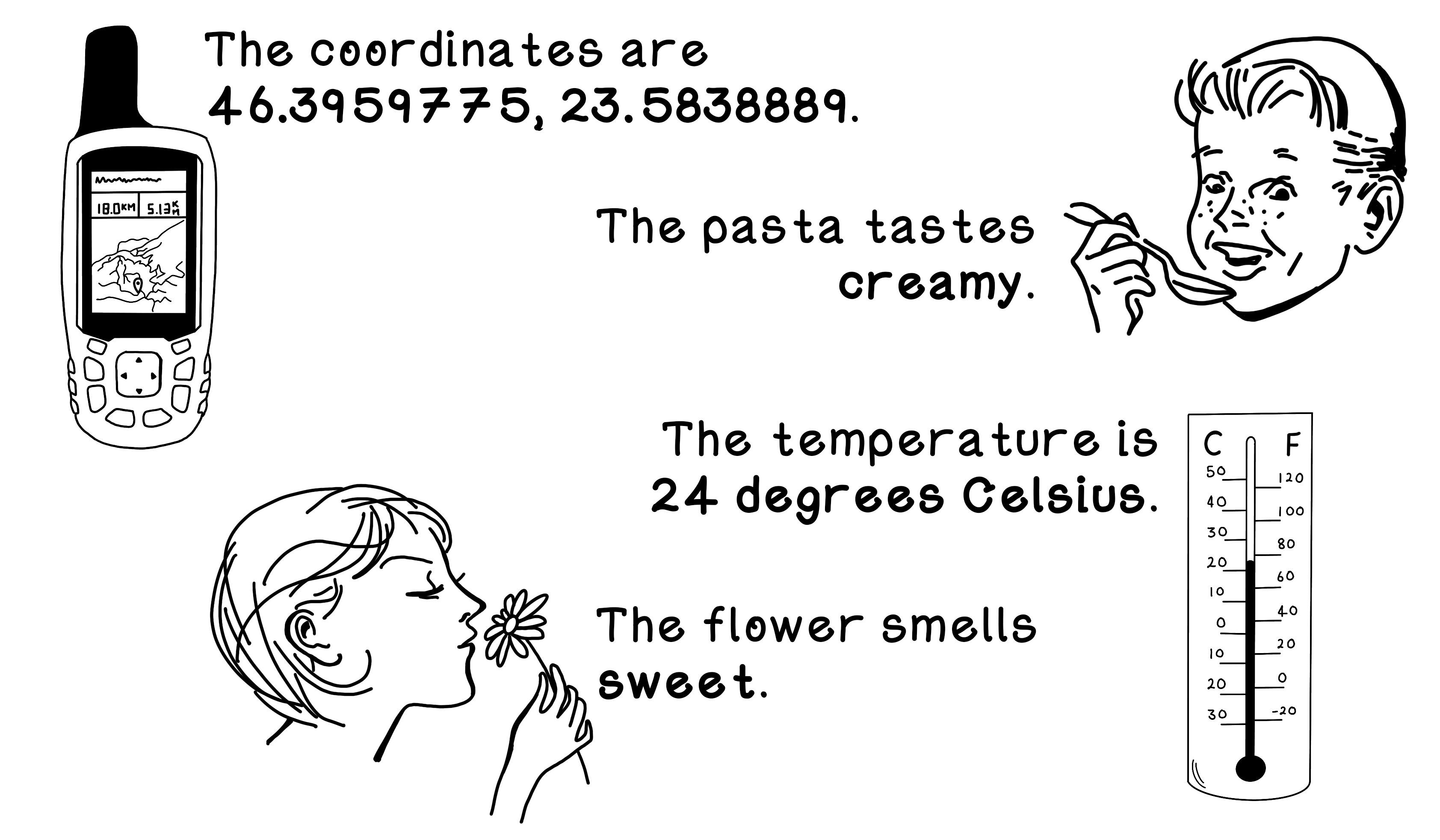

Data is the fuel for AI algorithms

Data is the fuel that makes AI algorithms work. With the incorrect choice of data, badly represented data, or missing data, algorithms perform poorly, so the outcome is only as good as the data provided. The world is filled with data, and that data exists in forms that we can’t even sense. Data can represent values that are measured numerically, such as the current temperature in the Arctic, the number of cats in a field, or your current age in days. All these examples involve capturing accurate numeric values based on facts. It’s difficult to misinterpret this data. The temperature at a specific location at a specific point in time is absolutely true and is not subject to any bias. This type of data is known as quantitative data. However, cherry-picking (or sampling) specific data points intentionally or unintentionally can create bias.

Data can also represent values of observations, such as the smell of a flower or one’s subjective review of a movie. This type of data is known as qualitative data and is sometimes difficult to interpret because it’s not an absolute truth, but a perception of someone’s truth. Figure 1.1 illustrates some examples of the quantitative and qualitative data around us.

Algorithms are like recipes

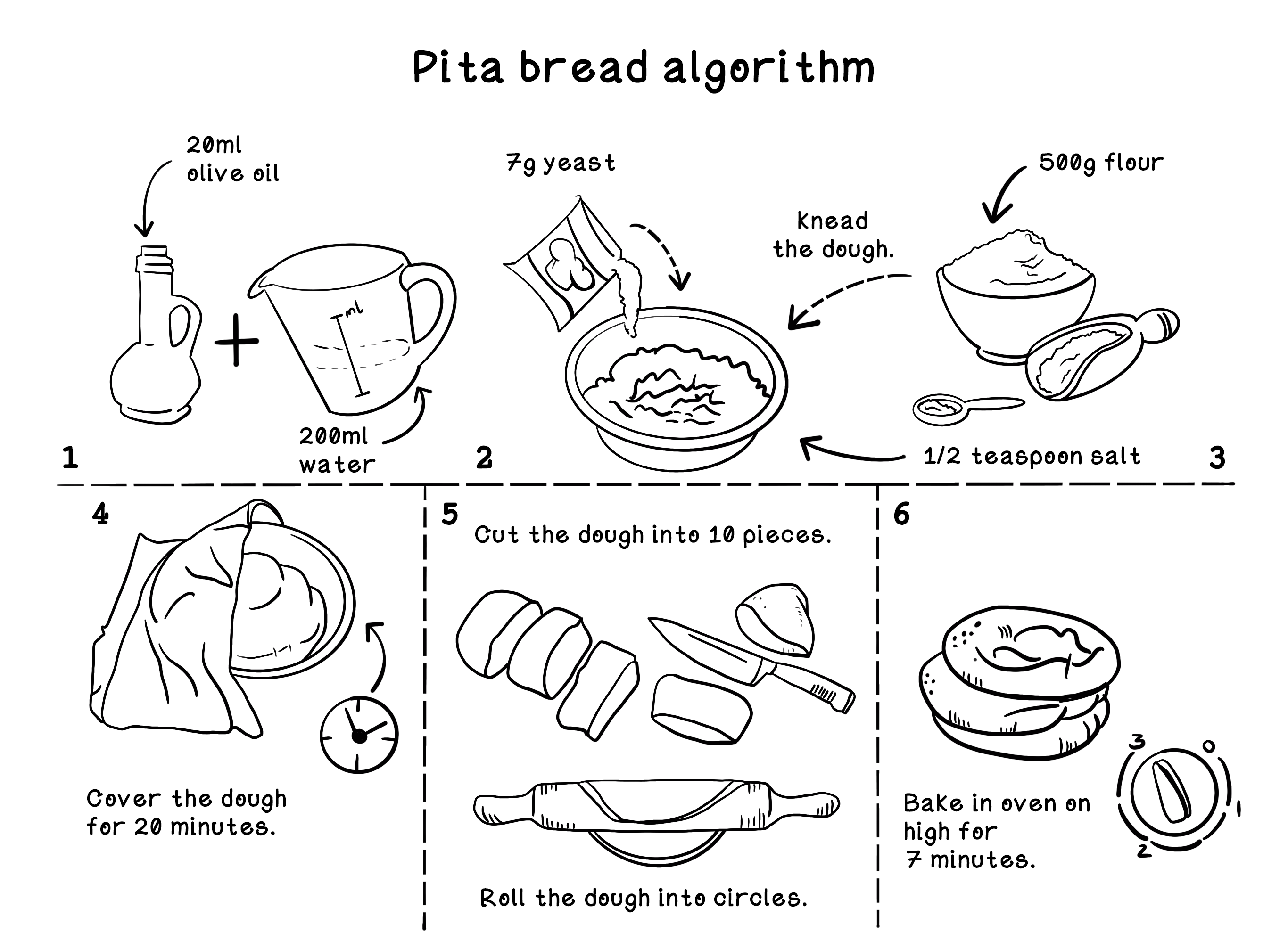

We now have a loose definition of AI and an understanding of the importance of data. Because we will be exploring several AI algorithms throughout this book, it is useful to understand exactly what an algorithm is. An algorithm is a set of instructions and rules provided as a specification to accomplish a goal. Algorithms typically accept inputs, and after several finite steps where the algorithm progresses through varying states, an output is produced.

An algorithm can be seen as a recipe (in figure 1.3). Given some ingredients and tools as inputs, and instructions for creating a specific dish, a meal is produced as the output.

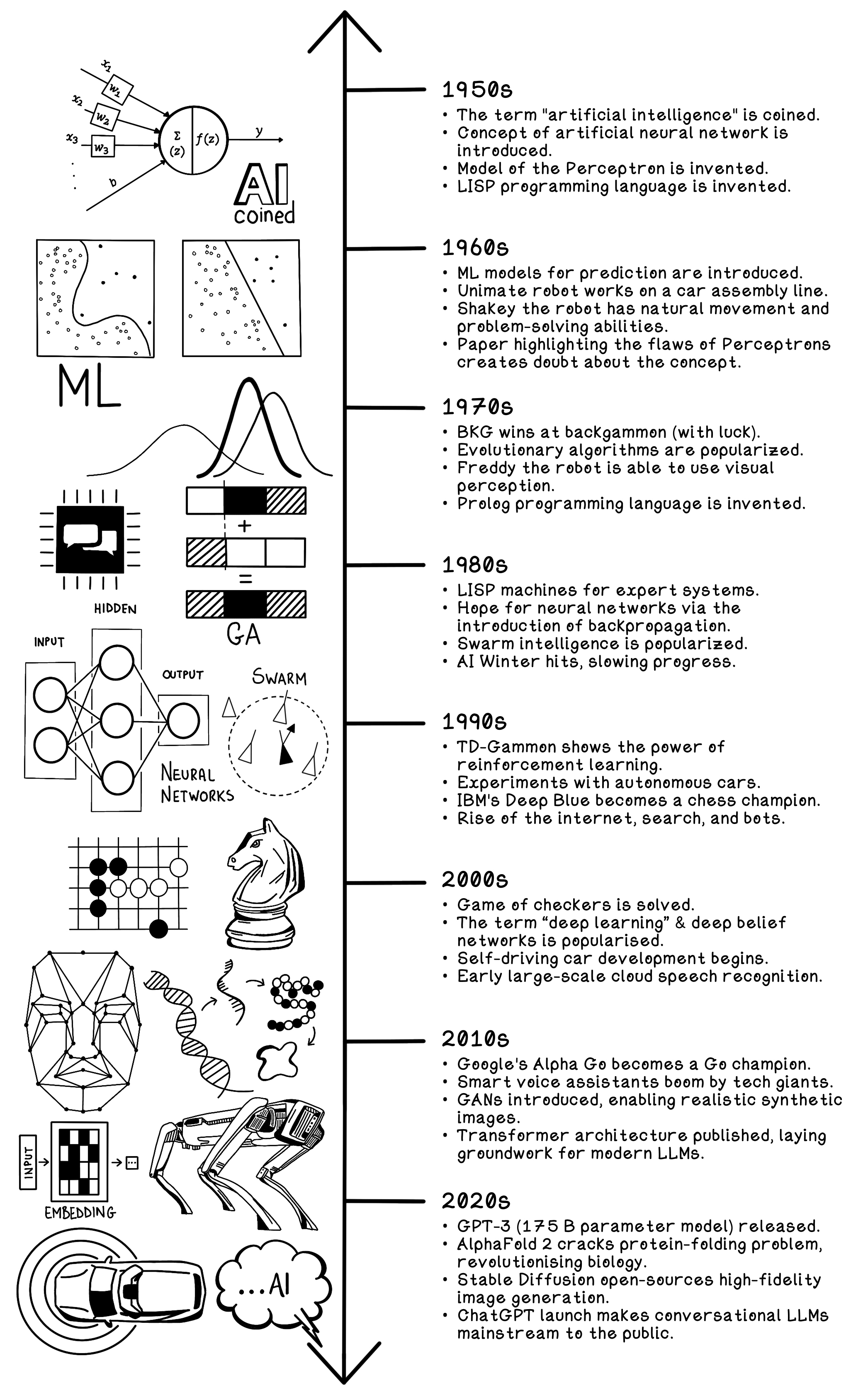

The evolution of AI

A look back at the strides made in AI is useful for understanding that old techniques and new ideas can be harnessed together to solve problems in innovative ways. AI is not a new idea. History is filled with myths of mechanical men and autonomous “thinking” machines. Looking back, we find that we’re standing on the shoulders of giants. Perhaps we, ourselves, can contribute to the pool of knowledge in a small way. Looking at past developments highlights the importance of understanding the fundamentals of AI; algorithms from decades ago are critical in many modern AI implementations. This book starts with fundamental algorithms that help build the intuition of problem-solving and gradually moves to more interesting and modern approaches. Figure 1.5 isn’t an exhaustive list of achievements in AI—it is simply a small set of examples. History is filled with many more breakthroughs.

Old AI and new AI

Sometimes, the notions of old AI and new AI are used.

Old AI is explicit logic and search that relies on humans to encode the rules of the world. The machine doesn’t “learn”; it calculates solutions based on logic and rules provided by programmers. A classic example is the Minimax algorithm in chess: the human defines how pieces move and how to score a board position, and the AI uses computational power and smart branching to search future moves and find the best one.

New AI is learning from data and flips the Old AI approach. Instead of being told the rules or how to score a situation, these models analyze vast datasets to figure it out themselves. A modern neural network playing chess, for example, isn’t following hard-coded heuristics; it has played millions of games against itself to learn patterns of victory that human programmers might not even understand.

We learn about both because, while search algorithms are often categorized as “Old AI” they are not obsolete. In fact, they are often paired with modern techniques to solve difficult problems. For example, Large Language Models utilize search strategies to determine the best sequence of words to generate. You need to understand the logic of search before you can understand how a neural network “searches” for an optimal solution. Figure 1.7 illustrates the relationship between some of the different concepts within artificial intelligence.

Search algorithms

Search algorithms are the bedrock of problem-solving. They are essential when a goal requires a sequence of actions, like navigating a maze or calculating the winning move in chess. Instead of brute-forcing every possibility—which could take thousands of hours— smart search algorithms evaluate future states to find the optimal path efficiently. We start our journey here: Chapter 2 covers the fundamental search algorithms, and Chapter 3 dives into intelligent search methods that strategize rather than guess.

Biology-inspired algorithms

When we look at the world around us, we notice incredible things happening in different creatures, plants, and other living organisms—like the cooperation of ants in gathering food, the flocking of birds when migrating, estimating how organic brains work, and the evolution of different organisms to produce stronger offspring. By observing and learning from these phenomena, we’ve gained knowledge of how these organic systems operate and of how simple rules can result in incredible emergent intelligent behavior.

Evolutionary Algorithms: Inspired by Darwinian theory, these algorithms use reproduction and mutation to “evolve” code that improves over generations. We explore this survival of the fittest in Chapters 4 (Evolutionary algorithms) and Chapter 5 (Advanced evolutionary approaches).

Swarm Intelligence: This mimics the collective power of “dumb” individuals acting smart as a group. Chapter 6 (Ant colony optimization) explores intelligent path finding inspired by ants, while Chapter 7 (Particle Swarm Optimization) covers solving optimization problems inspired by how animals flock.

Machine learning algorithms

Chapter 8 (Machine learning) takes a statistical approach to training models to learn from data. The umbrella of machine learning has a variety of algorithms that can be harnessed to improve understanding of relationships in data, to make decisions, and to make predictions based on that data.

There are three main approaches in machine learning:

Supervised learning means training models with algorithms when the training data has known outcomes for a question being asked, such as determining the type of fruit if we have a set of data that includes the weight, color, texture, and fruit label for each example.

Unsupervised learning uncovers hidden relationships and structures within the data that guide us in asking the dataset relevant questions. It may find patterns in properties of similar fruits and group them accordingly, which can inform the exact questions we want to ask the data. These core concepts and algorithms help us create a foundation for exploring advanced algorithms in the future.

Deep Learning

Deep learning is a broader family of approaches and algorithms that are used to achieve narrow intelligence and strive toward general intelligence. Deep learning usually implies that the approach is attempting to solve a problem in a more general way like linguistic intelligence or spatial reasoning, or it is being applied to problems that require more generalization such as speech recognition and computer vision. Deep learning approaches usually employ many layers of artificial neural networks (ANNs). By leveraging different layers of intelligent components, each layer solves specialized problems; together, the layers solve complex problems toward a greater goal. Identifying any object in an image, for example, is a general problem, but it can be broken into understanding color, recognizing shapes of objects, and identifying relationships among objects to achieve a goal. We will dive into how artificial neural networks operate in Chapter 9 (ANNs).

Reinforcement Learning

Reinforcement learning is inspired by behavioral psychology. In short, it describes rewarding an individual if a useful action was performed and penalizing that individual if an unfavorable action was performed. When a child achieves good results on their report card, they are usually rewarded, but poor performance sometimes results in punishment, reinforcing the behavior of achieving good results. Chapter 10 (Reinforcement learning) will explore how reinforcement learning can be used to train intelligent models.

Generative AI

Generative AI marks the shift from analyzing existing data to creating new content. Instead of just classifying an image or predicting a number, these models generate entirely new text, code, and visuals that have never existed before. Large Language Models (LLMs): We explore the architecture that revolutionized AI: the Transformer. Chapter 11 (Large Language Models) explains how these models master context and attention to converse, write, and reason with human-level fluency.

Generative Image Models: How does a computer dream? Chapter 12 (Generative Image Models) dives into the mechanics of creativity. We will look at how Diffusion models and U-Nets learn to sculpt pure random noise into structured, high-fidelity artwork.

We have now defined the fuel (data) that powers our systems and outlined the menu of problems—from prediction to optimization—that we aim to solve. But knowing the ingredients isn’t enough; we need to learn how to cook. It is time to move from definitions to implementation. In the next chapter, we will dive into Search algorithms—the fundamental logic that allows machines to navigate complex choices and plan their path to victory.